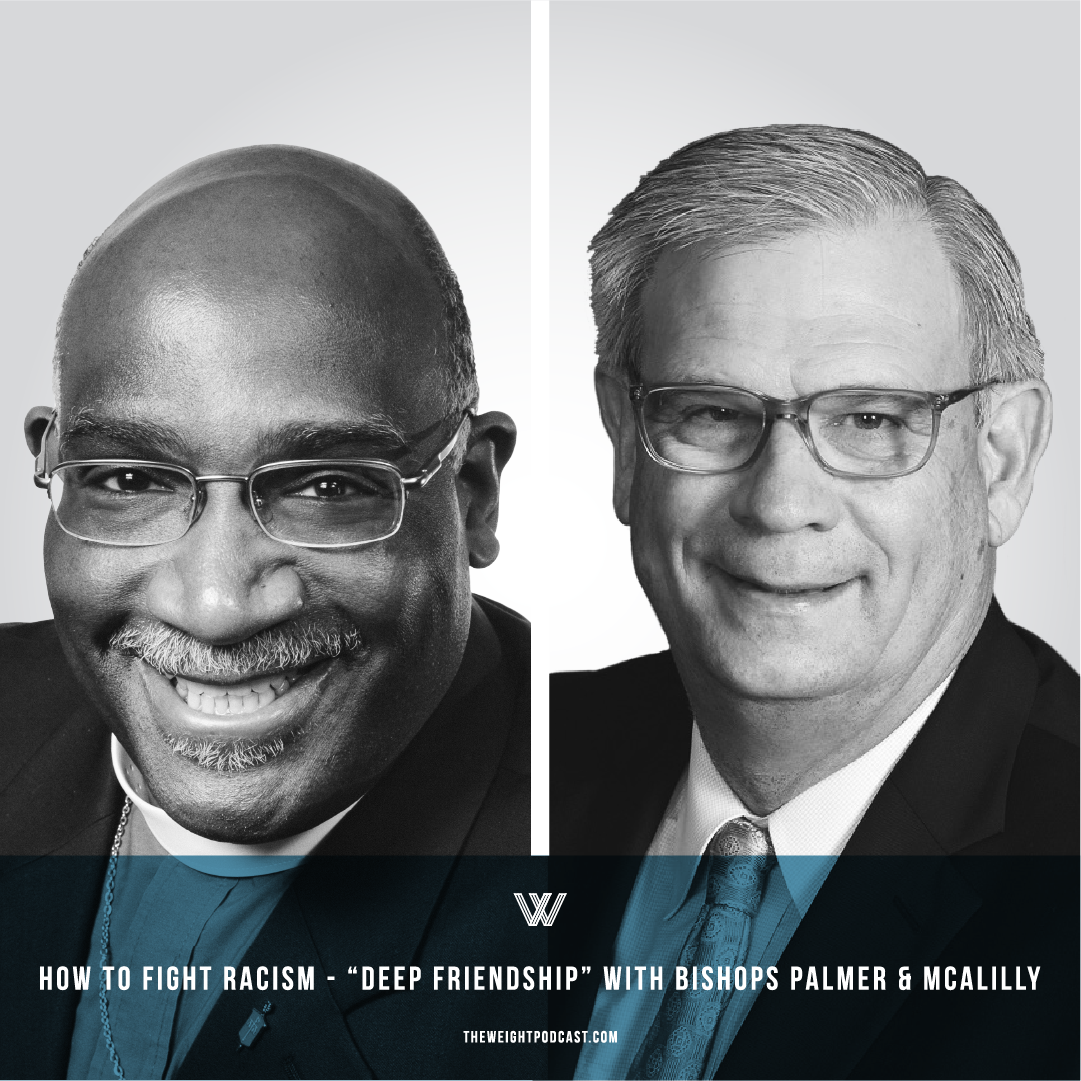

How To Fight Racism - "Deep Friendship" with Bishop Gregory Palmer & Bishop Bill McAlilly

Shownotes:

The year 2020 was a strong reminder that racism is not a simple problem of the past, and it cannot be met with simple solutions. At its core, racism diminishes the image of God in people of color, keeping them from living in the fullness that was God’s vision for humanity. How can we bring about true equity in our communities, churches, and in our nation? What are the practical steps that we can take now to bring about flourishing and reconciliation?

The Christian faith in America has never known a time when it has not wrestled with matters of race. These issues are a living, conscious reality for the whole life of the faith across denominations, and in order for us to make sustainable progress, we must move from silence to accountability and action within our church walls.

In this episode, Chris and Eddie are joined by Gregory Palmer and Bill McAlilly, two United Methodist Bishops who share a deep friendship that has been strengthened by honest and dynamic conversations about race and the church. Bishop Palmer and Bishop McAlilly urge us to think critically about what it looks like to love our neighbors, reflect honestly upon our history as a church and as a nation, and participate in multi-racial groups to discuss issues of race in a way that humanizes all of us.

Resources:

Learn more about Bishop Gregory Palmer here

Learn more about Bishop Bill McAlilly here

Check out Bishop McAlilly’s blog here:

https://bishopbillmcalilly.com

Follow Bishop Palmer on social media:

Follow Bishop McAlilly on social media:

Full Transcript:

Chris McAlilly 0:00

I'm Chris McAlilly.

Eddie Rester 0:01

And I'm Eddie Rester. Welcome to The Weight.

Chris McAlilly 0:03

Today we are talking to Bishop Bill McAlilly--he's my father--and Bishop Gregory Palmer, two bishops in the United Methodist Church. Now, the United Methodist Church is the church of which Eddie and I are pastors. But this is a broader conversation about race in America and the American church. And we kind of go back and talk a little bit about personal history, friendship, a cross-racial friendship, and we're continuing in this series on how to combat racism. And we go a little bit deeper today.

Eddie Rester 0:39

Yeah. Today, we get to hear from two men who have become friends. Beyond just their work together, there's a deep love and respect between them. And they share a little bit about how they hold each other accountable and encourage each other. And so I think it's an important conversation. One of the things that I've realized across my life is that I have to work harder, and Bishop Palmer shares a little bit about this. I have to work harder to make friends and deepen friendships with people who look different than me and who come from different backgrounds than me. And this is one of those conversations, I think, that encourages us in that direction.

Chris McAlilly 1:22

Yeah, we started this series with Jemar Tisby's book, "How to Fight Racism," and that book really framed the conversation around practical ways in which we can engage, and this continues that, you know, really thinking about friendship. And really thinking about how you exercise leadership in whatever your sphere of influence to affect some change. I mean, we were kind of honest about things have improved and things have regressed. You know, I think the power of language and storytelling comes through here and really just kind of, you know, getting to a deeper level of understanding about where you are, and kind of where your context, where you find yourself today.

Eddie Rester 2:08

So we hope you enjoy this larger conversation that we're a part of today. Be sure you share this, go ahead and leave a review. Subscribe to the podcast wherever you listen to your podcasts, and let let a friend know about it.

Chris McAlilly 2:22

[INTRO] We started this podcast out of frustration with the tone of American Christianity.

Eddie Rester 2:28

There are some topics too heavy for sermons and sound bites.

Chris McAlilly 2:32

We wanted to create a space with a bit more recognition of the difficulty, nuance, and complexity of cultural issues.

Eddie Rester 2:39

If you've given up on the church, we want to give you a place to encounter a fresh perspective on the wisdom of the Christian tradition in our conversations about politics, race, sexuality, art, and mental health.

Chris McAlilly 2:51

If you're a Christian seeking a better way to talk about the important issues of the day, with more humility, charity, and intellectual honesty, that grapples with Scripture and the church's tradition in a way that doesn't dismiss people out of hand, you're in the right place.

Eddie Rester 3:07

Welcome to The Weight. [END INTRO]

Eddie Rester 3:09

Today we're here with Bishop Gregory Palmer and Bishop Bill McAlilly. Welcome to both of you to The Weight today.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 3:16

Thank you.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 3:17

Well, thank you.

Eddie Rester 3:19

I feel kind of overwhelmed. We've got two bishops on the podcast with us, Chris.

Chris McAlilly 3:24

Yeah, it's a big day. You got to keep your act together.

Eddie Rester 3:27

Got to be kind today to everybody on the podcast. Well, we appreciate y'all's time. Y'all serve as bishops in the United Methodist Church and Bishop McAlilly, you serve in Tennessee, two conferences. Bishop Palmer, you serve in the Ohio West Conference in the Northeastern Jurisdiction. Is that right?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 3:51

Partly right, yeah, West Ohio. We're in the North Central Jurisdiction.

Eddie Rester 3:55

North Central Jurisdiction.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 3:57

Yeah. So we are on the jurisdictional, on several jurisdictional lines. But we're in the North Central.

Chris McAlilly 4:03

For folks that don't, you know, that are not kind of connected to United Methodism or even you know, connected to the church, talk a little bit about what a bishop is, what you guys do, and kind of what that role is in our church.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 4:20

You going first, Bishop McAlilly?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 4:23

You're a more experienced Bishop than me, maybe you know the answer that?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 4:28

Well, I would, I mean, this is both kind of a modest paraphrase of what our Book of Discipline, our book of policy, says, as well as a little bit of experience. But I think it's seriously that the bishops of the church, individually and collectively, are given spiritual and temporal oversight for the life of the church. That's acted out most significantly in residential areas.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 5:01

So like Bishop McAlilly has two-thirds of the state of Tennessee, and I have, you know, a little over half of the state of Ohio and a specific Annual Conference. And it runs everywhere from vision casting, to strategic implementation of vision initiatives, to the deployment of leadership, and our primary staff resource, obviously, over which bishops have the most influence are the clergy leadership. It's not the only place where we might have influence. And then we also have responsibilities throughout the connection. So through the Council of Bishops, and through the general church, through its programmatic and administrative agencies and institutions.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 5:53

Well said, Brother.

Eddie Rester 5:55

Anything you'd like to add there? Is that everything that you do?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 5:58

Well, you know, we do from time to time, we have to cause trouble and we have to solve problems that others who cause trouble for us.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 6:11

[LAUGHTER]

Bishop Bill McAlilly 6:11

But I think the great joy of the work is that we get to see the church at various levels, from the global perspective, to the US perspective, to the local perspective. It's a beautiful thing.

Chris McAlilly 6:28

Part of why we wanted to bring you guys on at this particular moment, and together, is because we're in the month of February, and we're talking about this longer conversation that's been going on in the American context, particularly with the church around matters of race, and you guys... I was in conversation with... So the other thing that you should know if you don't

Eddie Rester 6:51

If you haven't picked up on it.

Chris McAlilly 6:52

Yeah, that Bishop McAlilly is my father. So we have this long-running conversation about the life of the church. And we were talking, you know, during 2020, kind of in the wake of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor and other kind of larger conversations in the culture around race in the church. I was asking my dad kind of how he was thinking about these things. And there was a conversation that he said that he's kind of had ongoing with Bishop Palmer, cross-racial friendship. You were saying that, really, you guys, the friendship that you share at that executive level has been impactful.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 7:30

Oh, absolutely. Bishop Palmer and I discovered, probably, I don't know, three or four years ago, at about halfway into my first round as a bishop, that we had a lot in common. And we laughed at the same jokes.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 7:46

[LAUGHTER]

Bishop Bill McAlilly 7:46

And we had a similar interest in the world and in sports and food and those sorts of things. And we just hit it off. And we've gotten to work very closely together, particularly the last couple of years, and that's deepened our friendship.

Chris McAlilly 8:03

I wonder how you would describe--maybe each of you, if you wouldn't mind--kind of giving us a bit of your personal history, and maybe not the whole story, but maybe particularly around race. What are some of your first memories of race, as a young man growing up in Mississippi, Bishop McAlilly? And Bishop Palmer, I'm not exactly sure where you grew up, but as you think about kind of coming to an awareness of race, maybe I'll pitch it to you, Bishop Palmer, first.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 8:40

Sure, thanks. I was born and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And like many Boomers, my parents were, you know, first-generation college people who, they had gone to a historically Black college and university. My father on the GI Bill and my mother because her mother washed clothes and her father worked in a paper mill. And they were both interesting backgrounds. Both had roots in the South. My father, they were both born in Pennsylvania, but from a very wee infant my father was raised on the eastern shore of Virginia. So he was raised in a segregated society. My mother is from a small mill town in central Pennsylvania. And her parents are South Carolinians.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 9:31

And so I became aware, my consciousness around race really began with storytelling. And as I think back, my parents reading to me and the things that they expected me to read. I had the opportunity... I don't know a time that I didn't go to racially integrated schools. And so that was never not a reality for me. So I never went through public school, de-seg. But in many other ways my life was compartmentalized. All of my friends outside of school were people of color. And I went to a predominantly United Methodist African-American church, meaning United Methodist, but predominantly, and historically African-American.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 10:28

The other thing is I've got back to the reading thing of my parents, they, they always made sure that I knew those stories of African Americans that had excelled. And they were these you know, I had these books of short BIOS on people from George Washington Carver, to I was, you know, my mom helped me memorize poems by Langston Hughes County, Cullen, some of the poems of the poets of the great Harlem, Renaissance, etc. So that if the schools weren't doing that, they were making sure that I got sort of two flows of information, etc.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 11:12

The other thing, and then I'll quit on this, that really made me aware that we lived in a racialized world is that in 1956, when I was two years old, my parents moved from one section of the city, as apartment-dwellers in a predominantly Black neighborhood, to a community that we now would say was beginning to undergo racial transition. So they acquired their first home, etc, etc. And the conversations I remember--not when I was two, but soon thereafter--were looking at how on a street of a row houses, so that's the context in which I grew up in the city. People could, the African Americans could point to the houses that used to be owned by white people.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 12:04

So I became conscious that I lived in a racialized world because of white flight from the West Oakland neighborhood of Philadelphia. And there were never any big incidences that I that I recall, or that I heard about, but I would hear my parents and other neighbors saying, "Yeah, Ms. So-and-So used to live there before the Jones family moved in." So we watched our street, over a period of years, go from probably 100% white to 100% Black in due time. And the only whites, if any remained, were the elderly who couldn't get out because they had nowhere to go if they sold their home, no children to take them in or didn't necessarily want to move into a retirement community.

Chris McAlilly 13:00

What about you, Dad?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 13:03

So I did go to a segregated school up until the seventh grade. And when I went from elementary school to seventh grade, we were integrated, and my first experience was on the football field, and also the basketball court. I had been the starting point guard for the sixth grade basketball team

Eddie Rester 13:25

That's big stuff. Big stuff.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 13:25

at Fulton Grammar School. I was good. I think I had a point total of three points that year. And I went out for basketball my seventh grade year. Didn't make the team because Dale Stone and Phil Ewing and Harold Miller were on the team now. And they were all head taller than me in the seventh grade, so, and they could bounce around a ball. But my first awareness that I had entered a new world was my first day of football practice in the seventh grade when I went one-on-one with Dale Stone who ended up eventually getting a scholarship to play at Ole Miss in football. And I realized then I was in a new world.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 13:56

We quickly became friends. And we all, while we didn't hang out with each other after school, we did get along well in school. Then we moved after my seventh grade year, and my father became the district superintendent in New Albany, New Albany District. And there was an African-American District Superintendent, Merlin Conaway, who was on the cabinet. And Rev. Conaway's family and our family broke bread together in our home in New Albany, Mississippi, when I was in eighth grade. And that was the first time I had any experience breaking bread with a person of color. My father was very fond of Reverend Conaway, and they worked very closely together. And then during those years, this would have been the early 70s, my dad was working very closely to merge the North Mississippi conference with the Upper Mississippi Conference from the central conferences, which was the place where our African-American United Methodist churches were.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 15:12

And so, but you have to back... I want to tell a real quick story about my dad when he was in seminary. He went to Candler School of Theology, served a church in Mississippi his last year, near Tupelo, and he would hitchhike from Atlanta to Tupelo every weekend so he could preach. There was an African-American Methodist student at Gammon Theological Seminary from Aberdeen, Mississippi, which is just down the road from Tupelo. Israel Rucker was his name. Israel had a car. And my dad would get picked up by Israel while he was hitchhiking, and brought from Atlanta, through Alabama in the mid 50s. White man and Black man riding together through Alabama at night to Tupelo. And that was, that story has been one of the stories that taught me about the friendships that can exist.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 16:14

And so. Fast forward to 1970 when North Mississippi and Upper Mississippi conferences are merging, Israel Rucker and my dad at are on the stage and Annual Conference, standing side-by-side as the two conferences united, and they held hands and embraced. So those stories form my thinking about relationships.

Eddie Rester 16:38

So y'all have this long history. I mean, as we, you know, I grew up a child of the 80s. And so the stories that you tell of segregation and neighborhoods had shifted dramatically when I was growing up. And what I would ask both of you, as you think about your friendship forming on the Council of Bishops, how has that friendship impacted how you have lead as a bishop?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 17:08

I'd like to take a shot at that first, if I could. One of the things Bishop Palmer does is hold me accountable. You know, he doesn't let me off the hook for being timid and not speaking the truth around the matters of race. And when I have a question, or when I am struggling with some way of leading in my context, I'll often speak with Greg and say, "Greg, what do you think about this? Just help me understand what this means or help me understand this from your perspective," and that's enormously helpful.

Eddie Rester 17:42

Bishop Palmer, what about you?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 17:45

I would say a similar thing. We, I think we've, Bill and I, have created space for each other to have honest conversation, and even to make comments that might get a little bit toward the edges. And whether that's by text, or at a meeting, or, you know, in a phone call, I noticed that over time, our frankness with each other--not every conversation is not one of these, like, challenging people--but it's like not hesitating to say something quite as much saying, "Oh, my God, wonder if that's going to hurt his feelings? Or here's another place."

Bishop Gregory Palmer 18:35

And you'll have to see if this is true for you, Bill, I'm only thinking of this in reflection, but we know, or knew, some of them have gone on to get their reward some of the same people in common. And I have some of those that are African American, I didn't hesitate to give my opinion about how they functioned in the life of the church. That may be good or not so good. But you know, sometimes sarcastic, and I think Bill has made similar comments to me about colleagues. So it's like, if somebody is a jerk, they're a jerk, and if I could just be frank. And it doesn't mean we don't live in a racialized world, but we are growing our capacity to say, "That's jerk behavior". And, or to say, honestly, though we shouldn't seek this out, "You know, that person just really irritates me as a matter of personality. And they don't irritate me because I'm focused upon their race or ethnicity. They irritate me because, you know, they talk too much." You know, something simple like that.

Eddie Rester 19:52

Bishops talk to much sometimes?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 19:55

Oh, my gosh. Oh my gosh.

Chris McAlilly 19:57

Oh, man. Well, let me put this this friendship and y'all's relationship in a larger context. So, you know, Methodism in America, really going back to the late 18th century, like 1790s, has been struggling. Not just the United Methodist Church, which really, you know, for those of you who are not a part of that particular tribe only kind of gets off the ground in around 1968. But Methodism in America has been struggling around matters of race going back to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when Richard Allen stepped out and started the AME church.

Chris McAlilly 20:43

Bishop Palmer, maybe could you kind of give folks a bit of kind of the historical context, from your perspective on Methodism in America, and the, you know, just I guess the ways in which that history informs the present conversations.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 21:08

If I were to really laser in on a bull's eye, the summary statement for me is there has never been a time in American Methodism or the United Methodist Church and its predecessors where race has not been either on the table or under the table. So it's been a part of our lives, partly because the society was, as it was emerging, the US was structured in a certain way. And partly because of, even with the, let me say, the generosity theologically of the Methodist tradition and our founders, you know, they were too bound a bit, if not a lot, by some of the patriarchal language of the time. Just listening, looking at even how Mr. Wesley referred to, you know, Native American, indigenous people and the people of the African diaspora. But even in England, you know, John Wesley had interactions with people who were of ebony, who who were responding to the good news of Jesus Christ through the lens of the emerging Methodist movement.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 22:26

So, you know, we can't take ourselves out of our history. And it's always been a part of us and we've come at it in fits and starts. And sometimes that's taken people exiting from a wider, racially inclusive table, saying, "These conditions are intolerable." So if you take the brothers and sisters who exited St. George's, when their dignity--they just couldn't take their dignity being insulted anymore, that, you know, Black people can't pray or commune till all the white people have finished.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 23:04

And Allen, you know, went one way there are people who stayed under Bishop Asbury's leadership and formed the Mother African Zoar Church in Philadelphia. And of course, Absalom Jones became the first Episcopal priest and he was there, but they were all there at old St. George's in Philadelphia. So I want to say not to make it smoother, but Christian faith in America and the institutional Church has never known a time when it has not wrestled with race. So when I talk to Episcopalian colleagues, Lutheran colleagues, Baptists, you know, those in connectional churches and not connectional churches, it's been a living, conscious reality for the whole life of the Christian faith, as expressed on these shores.

Chris McAlilly 24:00

I think we're, I mean, we're sitting here in Oxford, Mississippi, and, you know, Mississippi is a unique context to be thinking about some of these matters. And then, you know, for you, Dad, growing up in Mississippi. I think, for me, I really began to struggle with the more systemic dimensions of racism within the institutional church when I graduated college, and I was living in Nashville, and I met James Lawson, who was training to be a Methodist pastor at Vanderbilt during the sit-in movement in the 60s, and was kicked out of Vanderbilt. And he had been invited back with a doctorate and visiting professorship, and it was at that time that I started really reading the history of the Mississippi Conference and some of the things that had gone on.

Chris McAlilly 24:50

And one of the things that I've learned is, you know, there was a time where, you know, college students from Tougaloo College were barred at the doors from breaking bread, the Communion table at Galloway United Methodist Church in downtown Jackson, right across the Capitol. And I think, you know, as I've moved on from that moment and had lots of conversations, we've had conversations about this through time, I think, you know, one of the things you realize, if you grow up in the church or not, is that the church is a human institution, and we've got jerk-like behavior running through our history. And there are problems in the institution that are partially there because human beings are broken, and we inherit certain things from our history.

Chris McAlilly 25:38

I wonder for you, Dad, as you've kind of wrestled around these matters, and then now serving at this institutional level in executive leadership, how have you been attempting to either address some some matters that you see? Or what are some of the things that you lament that have been difficult to address? And then, you know, what are some of the ways that you see Bishop Palmer doing the same? Bishop Palmer, I would love for you to weigh in as well.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 26:04

That's a good question. You know, what I understand, as Bishop in Tennessee, is that the South is still very much racially motivated. And it's, while we have more opportunity in some ways of cross-racial appointments, for instance, in Tennessee than I had in Mississippi--I was only able to make one cross racial appointment when I was a district superintendent on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. And we haven't had a high number of those in Mississippi over time. But I'm finding a little more openness to that in Tennessee.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 26:46

But I've written some things in my conference blog around racism over the last several months, and the vitriolic response that I often get from some of those statements, really, is quite alarming, frankly. And I had, I wrote a statement, SEJ bishops wrote a statement on racism in June, and I had a group of people that had walked out of a church, a white church, because the pastor read the statement that I wrote, or that we wrote, and that was just heartbreaking and shocking, frankly. I had one small membership church that just decided they didn't want to be Methodist. "We're not United Methodist anymore because of our stance on racism." And so it's just heartbreaking to think that we're in 2021 now, and we still are wrestling, in some ways, as much as we wrestled in the 60s.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 27:54

And yet, I've seen glimmers of hope, here and there. And in fact, we're in the appointment-making season in our tradition, which means for those who aren't United Methodist, is that we play fruit basket turnover with preachers and churches, right. And so one of my county seat churches in West Tennessee, a college town, has said to me, "We would be willing to receive a Black pastor. We'd be willing to a female pastor," which that also is a challenge still in the south. So that's progress, from my perspective, that you see the the regression in some ways and then you see the progression in other ways. So it's a very interesting time.

Eddie Rester 28:40

Bishop Palmer, what about you? What do you see from your vantage point?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 28:44

Um, I do see marvelous signs over time of progress made. And I concur with Bishop McAlilly that sometimes the regressiveness that I've seen... I almost go to sleep, and then I wake up, sort of shocked that that happened. And I really, I really shouldn't, really shouldn't be. So I don't want to poo-poo anything that is better and is different for the better, but we are not yet over the mountain. I want to say this is not Jim Crow. This is not some of the more fierce times, yet that makes it more frightening, because it appears to be more subtle.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 29:38

And in the last couple of years, and if you look at some of the racialization of what happened on January 6 in the nation's capital, you know, and the disparities there, or what happened at the Michigan Capitol several months ago, there's just no way that a group of armed or unarmed people of my hue could ascend in a mob form on the steps and into the building of a Capitol, state or federal, and blood not be running everywhere. It's just, I mean, not in a nation where a police officer can put his knee on someone's neck or chest for eight minutes and 46 seconds.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 30:27

So I'm hugely conscious that we've made enormous strides. And it's like, where did that come from? And so there's this tremendous fear that I believe people have taken in the Kool-Aid that, as we hurtle towards stats that say this nation will no longer be predominantly Euro-American, that that's a bad thing. I mean, as opposed to saying, it's becoming what it's becoming. It's more complex, more diverse. What are the gifts of that? So we see that as a problem. And that's the underbelly of white supremacy.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 31:11

And I know that's a challenging word for some people. I tried to say to a group the other day that, you know, when somebody uses the word "white supremacy," it doesn't necessarily mean they're saying to a white person or a white audience that someone assumes you hate all people that aren't white. It's more pernicious than that. So that supremacy is that the plumb line and the value system of what is good, what is excellent, what is beautiful, and what is possible, is defined through the lens of whiteness, and everything else is second and third class, at best, from beauty to anything else.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 31:53

So we've got some work to do and it has reawakened I trust the nation. But there's a lot of fear of retaliation about the way in which some people are being treated, that we've got to try to come up against that fear on the part of those who believe they're subject to be attacked, because they're going to be painted with the same brush. I refer to my Anglo sisters and brothers. And I want the fear to be out of the system of our lives so that if I get stopped for my taillight being out, I want there to be--and I don't have my clergy collar on or I'm not wearing a Brooks Brothers suit--I want there to be a great likelihood that I'll get home alive that night.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 32:52

And I knew things were bad two weeks ago, when Anglo lay people in this conference that I've come to know better than some others, who are over 70, started asking me directly, "Are you safe?" Because I figure they're hearing conversations that I don't hear.

Eddie Rester 33:13

Right. Right.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 33:14

One woman, one woman over 70 texted me and said, "Bishop, please wear your clerical wherever you go. Just as a guard." This is two weeks ago.

Eddie Rester 33:25

I think what you said a few minutes ago is it's subtle. And that's the challenge right now. It's not the blatant Jim Crow era. It's not the 60s with policemen unleashing dogs and fire hoses. There's a much more subtle conversation, and maybe that, in some ways is a positive. We've moved to the place where we really need to talk about some of the deeper, lasting issues that are holding us back as a people and as followers of Jesus, in dealing with those subtle things.

Eddie Rester 34:08

What I guess I would ask the two of you is, how do we, from your vantage point, from what you have seen, listening to followers of Jesus and talking to people, what is there to do? Maybe, what are you seeing being done that's really helping people get at the root and bring healing and life into our world?

Bishop Bill McAlilly 34:36

I have a church in Nashville, McKendree, which is named for Bishop McKendree, who was the follower of Francis Asbury. So it was a historical place, served by Stephen Handy, an African American pastor, predominantly white church. And they did a 12-week online study on how to be an anti racist this summer, which my wife Lynn and I participated in. And it was fascinating to be in those conversations. Many millennials were on the call, but there are also some folks that were our age and older. But it opened up space for some honest dialogue, and I think, in a pretty non-threatening way, but also taking seriously the dilemmas of racism in our culture. I think that's one of the things that I see is how do you have honest, open, frank conversation with people from all walks of life on the call.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 35:42

I think that naming... I always have that my fear is if you can name a problem, you can deal with it. Put it on the table. It doesn't have as much power over you, if you can put it out. Make it conscious rather than unconscious. And then what I find is, many, many white folk in Mississippi, the South, have friendships with persons of color. And so that's not the problem. The problem is when it's an institution or a collective body, where people project onto that group certain negative images, and they see that as the problem. You know, so that I guess that's just... and so we're trying to have those conversations. We're trying to do that work well. We are committing to broadening the racist conversations, anti racist conversations in Tennessee.

Eddie Rester 36:43

Bishop Palmer, what about you? What do you, what is it that at the local level, we can be about and do? What have you seen that is helping people make progress?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 36:54

I would say things such as Bishop McAlilly described: people coming together in a multi or interracial or multiracial group discussing these challenges. I think our greatest influence is going to be within the church and in the Christian community--I hope not our only influence--and I do believe, I don't want to become cliche, and I'm not that pious, but I think we got to have this conversation, so to speak, at the foot of the cross.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 37:28

I think secondly, and this is where you all mentioned Jemar Tisby earlier, I can't remember if you were recording, or we were leading into the recording, but you know, a part of his own call to write the two books that he's put out in the last 18 months, are about the failure of the so-called evangelical community to take race seriously. And to take it on as, you know, we wrestle not with flesh and blood with but with principalities and powers.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 38:09

And so I think it's got to be named, as Bishop McAlilly has said. And, you know, I think it's going to take the courage, for example, that the bishops of the southeast took on under some threat to themselves. I mean, Bill has described to me some of the letters he's gotten, and they are obscene. They are literally obscene. And anybody who says that they know Jesus ought to be ashamed to write that letter.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 38:39

We all have a letter that we've written in our heads that we've never sent. So I don't want to, again, I don't want to act holy. But the idea that they actually thought it, then wrote it, then sent it. I'm saying, where's the restraining--I'm quoting from the liturgy--there's restraining and renewing influence of the Holy Spirit in our lives, or, in fact, have we missed Jesus altogether? So it's got to be named.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 39:06

Here's the third thing. I think the other thing that's got to be named and this is all can be done locally, not just need to come from the Council of Bishops per se. We got to get over the delusion that we live in an integrated society. And, I think that's a truth. We, everybody can say, "I have friends who are from a different tribe, a different racial ethnic group, maybe even a different zip code, maybe unlettered, or lettered if I'm unlettered," so to speak. But in the main, across racial and cultural lines, and this is not just a Black and white thing: We don't do life together.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 39:53

You know, our zip codes have a tremendous amount of segregation in there and I understand there's a preference from multiple communities to sort of stay enough to your own. Some communities, particularly immigrant communities, say because we want to reinforce some cultural norms. So it's less about, you know, "we're mad at anybody" and more about, "we want to transmit our stories, our language, and some other things." I mean, so I get that that's complex, but we are not doing life together. So I live, I work in a world that is predominantly Anglo, if you just look at the constituency. When I have to test my circles of friendship that are not driven by work, they are not substantively people that are not Black. Now, part of that is, you know, because of where I work and how I work institutionally, I have to work at making sure I have African American friends, if you understand what I'm trying to say.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 41:06

And part of that's a problem with ministry, by the way, that, you know, where all of your friends come from your work setting, you know what I'm getting at. So if my work setting is predominated, then I've got to work harder at the other thing, because that's not where I'm living. Just, if you take the hours in a day, the hours in a week, that's not where I'm living my life. So you are most likely to develop warm, loving, affectionate friendship relationships with people that you're around more. That's just... It's just arithmetic. And so there's no bad people, including me.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 41:43

So how do I not lose a sense of... So I don't want to lose or not have Bill McAlilly as my friend or you know, any folks here in West Ohio, but I want to not be... I don't want to look up at 70 and say, "Man, I don't have any friends that look like me." Not because friendship is not friendship. It's like, what's the message to me? What would be the message to children or our grandchildren? And I've been raised and formed to function, live, and lead and serve in a diverse world. I do not want to live in a monochrome world. Not monochrome Black, not monochrome, white. So actually, it's a contradiction if I don't have any friends that are not from multiple tribes, so to speak, and pigments, to my values that may be more than you wanted, guys.

Chris McAlilly 42:46

That's great.

Eddie Rester 42:47

That's good.

Chris McAlilly 42:47

That's great. Yeah, we, you know, we just have a couple more minutes here. I wonder if we could wrap this conversation up by basically asking both of you, what are your fears and your hopes for American Christianity, especially around matters of race, here at the end of your career in ministry? As you think about the church that your children or grandchildren will inherit, what are your hopes? What are your fears and what are your hopes?

Bishop Gregory Palmer 43:21

Sure, my greatest fear is that we'll demure when the work gets too hard. And my greatest hope is that all of us would be in the continuing, ongoing process of surrendering our lives to Jesus and to the good news of the gospel.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 43:45

It's hard to improve on that now. Yeah, I think my fear is that we'll just shrink back and we won't take it seriously, and we'll just say it's just too hard, that's what Bishop Palmer was saying. My hope is that we believe the scripture that Jesus said in John 14, the greater things are yet to come. Greater things are still to be done by those who are faithful and trust and believe. And so that's just kind of amplifying what Bishop Palmer said about believing the gospel and living it. I say our greatest hope is that we love God and love neighbor. And we have got to get the neighboring piece right.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 44:33

Yeah.

Eddie Rester 44:34

That's good stuff. Well, maybe the word as we head out from this episode is for each of us to begin to pray and to think about the greater things to be done. What is God calling us to in our places of influence, in our circles, to begin to pray and talk about how can we be a part of bringing the kingdom alive where we are around these issues, these important issues of race?

Eddie Rester 45:03

Bishops, thank you for your time today. I know y'all are very busy, took some time away from other meetings to be with us. So thank you all for that.

Bishop Gregory Palmer 45:12

Thank you. I'm actually reinvigorated. All right! Yeah, I'm ready to go now.

Eddie Rester 45:18

And we've been promised that we're gonna get one episode with Bishop McAlilly, just Chris McAlilly stories, so we're gonna hold you to that.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 45:24

Oh, good! Good. I look forward to that.

Eddie Rester 45:26

Probably be our best episode.

Chris McAlilly 45:28

Yeah, it's gonna be in 2020 what?

Eddie Rester 45:32

27 I think. 2027.

Chris McAlilly 45:34

Something like that.

Eddie Rester 45:34

Thank y'all very much.

Chris McAlilly 45:35

Thanks a lot.

Bishop Bill McAlilly 45:37

Thanks. Okay.

Eddie Rester 45:38

[OUTRO] Thank you for listening to this episode of The Weight.

Chris McAlilly 45:42

If you like what you heard today, feel free to share the podcast with other people that are in your network. Leave us a review, that's always really helpful. Subscribe, and you can follow us on our social media channels.

Eddie Rester 45:54

If you have any suggestions or guests you'd like us to interview or anything you'd like to share with us, you can send us an email at info@theweightpodcast.com. [END OUTRO]